Why Stories Exist

If entertainment researchers knew why stories existed their concepts would be even more useful to industry practitioners.

In many countries, after work and sleep, entertaining stories are what people spend most of their time doing.1 Given this salience of fictional, entertaining stories in our lives, it’s kind of weird most researchers and practitioners don’t even know why they exist.

People think they know why these stories exist though. The NYT did a piece last year focusing on trying to answer this very question with key figures from literature, arts, and sciences. None of those key figures got the answer right. (Maybe multiple interpretations of the same question?) Their answers focus on making meaning, empathy, and connection, deciphering patterns in the world, and finding truth through mental play. The audience “gets something” out of stories, said these key figures in the article.

I have personally noticed that other people stick with audience-centric explanations like those above when talking about why stories exist. Communication researchers refer to Harold Lasswell, who identified stories’ ability to help surveil the environment, interpret the world, and transmit social heritage. Philosophers refer to Jürgen Habermas, who identified stories’ role in democracy’s “public sphere.” Or they refer to Freidrich Schiller, who identified moral conflicts in stories as a mechanism that helps society work through its difficult dilemmas. Indeed, asking ChatGPT “Why do stories exist?” yielded a list of bulleted audience-centric reasons segmented into psychological, sociocultural, educational, and therapeutic headings. Its answers remained audience-centric when I added two words to the question “Why do fictional, entertaining stories exist?”

Figure 1. Created with model SDXL 1.0 on Nightcafe with prompt “Episodic memory in the human brain.”

Some people have tried to explain stories’ existence by referring to how human memory works. A few conversations with academic colleagues make me think this might be a widespread, weakly articulated assumption in academic circles. If there were any logic behind the assumption, it might go something like this: The human mind naturally organizes many memories into stories. It’s called episodic memory. For example, if I ask you what you ate for lunch two days ago, you’ll probably answer me by mentally “rewinding” the movie of your life — the time, place, location, and feelings — so you can access that information. And so, the logic goes, stories are some type of innate response to our environment to help us communicate, and their structure mirrors episodic memory. This narrative-like way we store memories is indeed part of the answer, but it cannot explain why fictional, entertaining stories exist in the first place.

Lastly, scientists also know stories “co-opt” certain aspects of our minds. Stories are built out of smaller creative innovations called super-stimuli (e.g., sexy bodies, car chases, clown faces, fast-cut pacing techniques, and zombies are all unnaturally attention-grabbing — hence the label super stimulus). The idea here is that stories hack our brains’ way of interpreting the world to entertain us in ways reality cannot, and so stories are sort of “byproducts.” This byproduct idea has been used to explain stories’ existence. However, this byproduct explanation — by itself — also fails to explain why stories exist in the first place. 2

Figure 2. From Wikipedia — The Venus of Willendorf above is an example of a human-created super-stimulus — it’s the example shown on the Wikipedia page for super stimulus. The body and breasts are exaggerated and co-opt instinctual aspects of human perception. Stories contain many such super-stimuli.

Although stories do perform all of the functions and elicit the responses above, none of those is the reason fictional, entertaining stories exist in the first place.3 The real reason has profound importance for people who are trying to measure things about TV and movies.

Entertaining Stories Exist Because Storytellers Want Your Attention

The answer starts by acknowledging that such stories exist for the sake of the storyteller. Stories are technologies that are for entertaining people to get their attention.4 Stories are not truly innate, but rather a specific type of creative invention. This idea that stories are actually technologies explains why TV and movies are filled with exaggerated features (car chases, special effects, rapid-fire jokes, monsters, innovative pacing techniques). It also explains why TV and movies have gotten better at depicting these super-stimuli (and creating new ones) over time incrementally. It’s because storytellers are like a group of scientists (albeit very disorganized ones) co-developing the technology of story and making it better and better over time. Imagine what could happen if they actually put in a coordinated, systematic effort.

The quantitative entertainment scholars (actual scientists) have the know-how to make this systematic effort happen. But traditionally, these scholars focus on important audience-psychology outcomes, such as mood management, enjoyment, appreciation, character likability, moral development, audience self-expansion, and immersion. Although some researchers do focus on persuasion theories interlaced with narratives, they are not focused on developing story as a technology. The audience-centric outcomes of academic scientists are still important to this storyteller-centric paradigm, but other outcomes pop out as well that seem directly relevant to developing the “technology of story.”

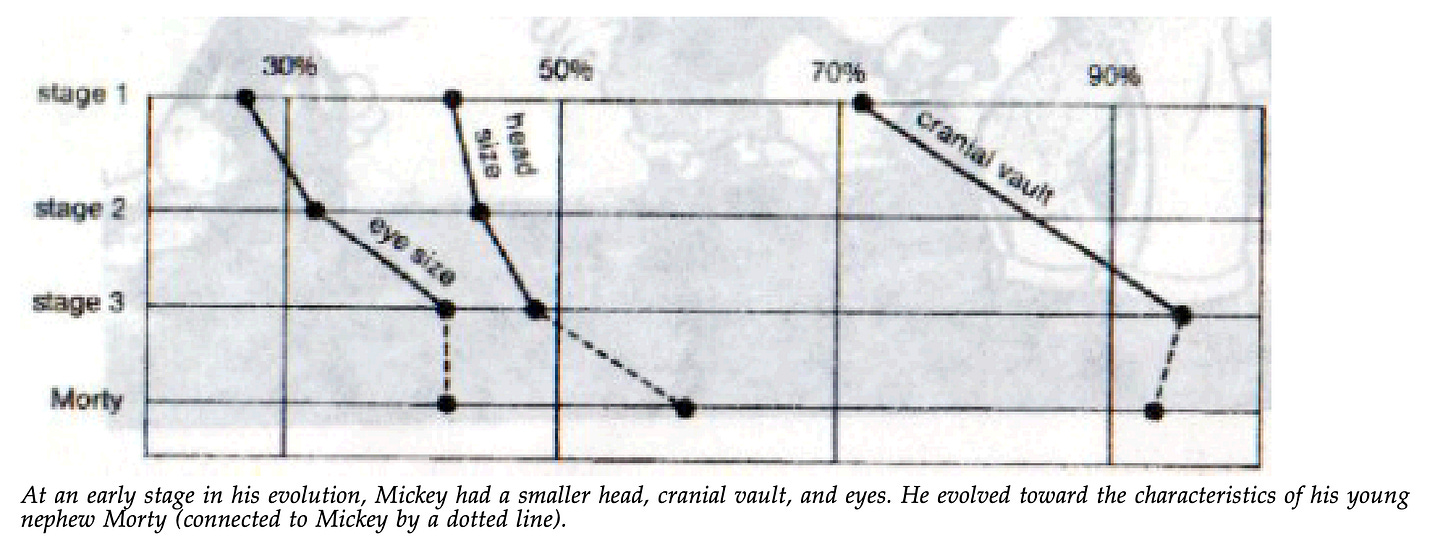

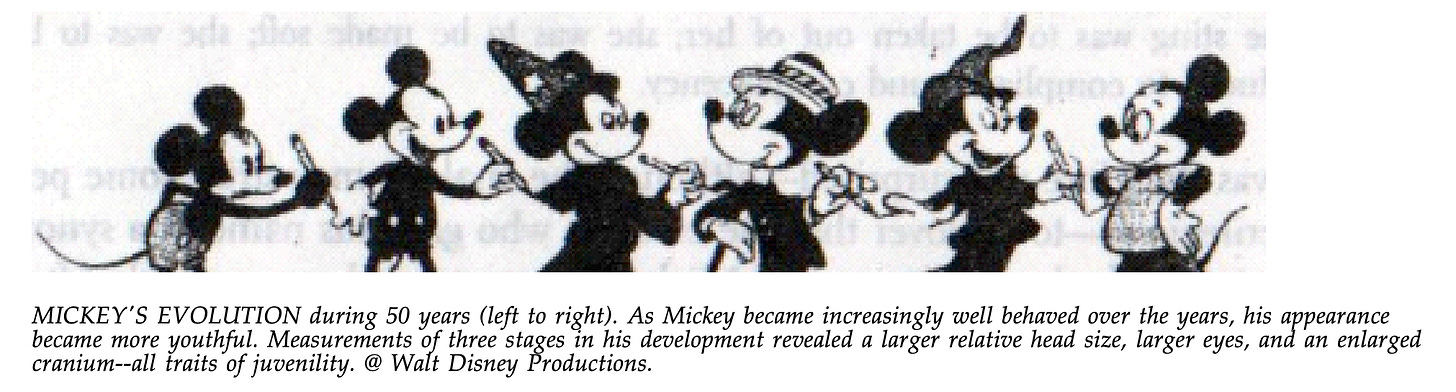

Figure 3. Mickey Mouse became more of a super stimulus over time hijacking our empathy for young children with his physical features. - from: https://faculty.uca.edu/benw/biol4415/papers/Mickey.pdf

Conclusion: Why is this perspective important for story metrics?

Story elements that we measure — when defined as technologies for the storyteller — lead us to look out for certain concept categories more so than does the “audience effects” lens most researchers take. As I mentioned, story elements can act as (a) superstimuli, (b) psychological nudges, or (c) design principles that exploit our minds to get our attention. From a storyteller's point of view, these elements are the technological bits from past stories they can remix to create a new story. Rather than cataloging and measuring audience responses, the story researchers’ job now shifts its focus slightly toward building useful concepts and tools for storytellers.

This has a few different consequences. First, academic researchers can get inspiration from (adopt, adapt, refine, and debunk when necessary) storyteller vocabularies (such as those from screenwriting literature). This is a logical starting point when initiating a research program around building the technology of story. Science always starts off noisy and uncertain, with bogus categories and concepts that exist until someone proves them wrong. It’s completely fine for scientists to start filling in gaps in theory with the folk-understandings of good storytelling and then evolve the science from there. Second, to guide this effort, these storyteller vocabularies can be integrated with theories that come into play when analyzing things like superstimuli or nudges: evolutionary psychology and adaptive mismatches, loss aversion, heuristics & biases, etc. In order to be useful, a coherent framework for these “story as technology” pieces should identify the concepts, their respective metrics, and their relation to audiovisual features or script features of content. Third, the key piece that ties the different “story as technology” pieces to actual audience outcomes. This is where existing entertainment and marketing research can guide how to map these story-as-technology features to audience responses like moral judgment, enjoyment, and appreciation — in addition to using techniques like revenue modeling, forecasting, and portfolio analysis to account for business metrics (e.g., box office, social-media popularity, series longevity, awards). Existing entertainment theories and marketing research can play the role of tying these elements together.

Scientists (pretty much all kinds of them outside the social and psychological sciences) focus on innovating on technology in addition to their theoretical work. They even innovate on commercial tech. Rocket scientists make rockets. Electrical engineers make circuits and robots. Physicists innovate on fusion energy. Entertainment researchers need to get over the hurdles blocking them from helping the industry and start learning real lessons about quality storytelling. This story-as-technology framework clarifies what some of the bounds of the scientific endeavor should consist of. Specifically, it’s incomplete to think about stories without having the storyteller in mind. Bringing quantitative, systematic effort to developing story as a technology could be the biggest public service of the academic discipline of media entertainment studies.

In sum, the paradigm shift from focusing solely on the audience to considering the storyteller's intent and techniques is essential for advancing our understanding of why stories exist and how they function. By viewing stories as "technologies" designed to capture attention, we can better quantify the elements that contribute to their success and broaden the scope of research to include the storyteller's strategies and goals. This multi-faceted approach not only refines our metrics and analysis for evaluating story content but also holds the potential to revolutionize the entertainment industry's approaches to crafting and monetizing compelling narratives. As we move forward, linking these elements in a coherent framework will provide invaluable insights, ultimately benefiting both the storyteller and the audience.

see also https://www.statista.com/statistics/186833/average-television-use-per-person-in-the-us-since-2002/

My own research posits that stories can induce a shared mental rhythm within a group, priming it for collective action. I concluded a series of studies affirming this concept, speculating: “We suggest that coordination of mental events explains these findings, and describes what is perhaps a core social function of mediated narratives.” Initially, I meant this as an explanation for why stories exist. While I now refute this reasoning (but continue to acknowledge that stories facilitate synchronized mental activities within a group), it doesn’t elucidate the presence of fictional and entertaining narratives.

A counterpoint is that research has indeed shown the persuasion can be more effective when told in fictional-story form. But when analyzed, this observation actually strengthens the overall point that stories exist for the sake of the storyteller. Here’s a cite below if you’re interested. Several concepts become relevant in more recent research (character identification, transportation, immersion, psychological flow) all of which seem to take the audience out of argumentation mode and into persuadability mode.

Slater, M. D. (2003). Entertainment education and the persuasive impact of narratives. In Narrative impact (pp. 157-181). Psychology Press.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.786770/full#ref1500